Drug delivery is the science and practice of administering a pharmaceutical compound1. Its goal is to get the right drug to the right place in the body at the right time and in the right dose to produce a therapeutic effect. It connects pharmacology, materials science, and clinical medicine, and has fundamentally transformed how many diseases are treated.

This comprehensive interdisciplinary field covers both the route of administration, such as oral or injectable, and the design of systems like tablets, patches, or nanoparticles that control how the drug behaves in the body. A drug delivery system is any formulation or device that presents a drug to the body in a controlled way. Common examples include coated tablets, prefilled syringes, inhalers, transdermal patches, depot injections, liposomes, and other nano‑ or micro‑particles2-8.

Why drug delivery is important

Good drug delivery improves how well a treatment works and how safe it is. It can enhance drug stability, increase the fraction of drug that actually reaches the target, and smooth out blood levels over time to avoid peaks and troughs9-11.

It also aims to improve patient experience 6. Optimized drug delivery can reduce how often a patient needs a dose and minimize side effects on healthy tissues, making the treatment more convenient and thus improving adherence and overall outcomes12.

Basic concepts in drug delivery

Several core concepts guide the design of any drug delivery approach. Key ones include:

- Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics: A drug delivery system should shape absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion efficiently, to ensure that the drug levels stay in the therapeutic window while achieving the desired effect at the target site13.

- Specificity and targeting: Where possible, the system should preferentially deliver the drug to diseased tissues, such as tumors or inflamed organs, and spare normal tissues14.

- Controlled release: The formulation can be designed for immediate, delayed, or sustained release depending on the condition and the drug’s properties15.

- Biocompatibility and safety: Materials used in delivery systems must be non‑toxic, non‑immunogenic, and, when appropriate, biodegradable 16-17.

Major routes of drug administration

A route of administration describes where and how the drug enters the body. Each route has its characteristic advantages and limitations.

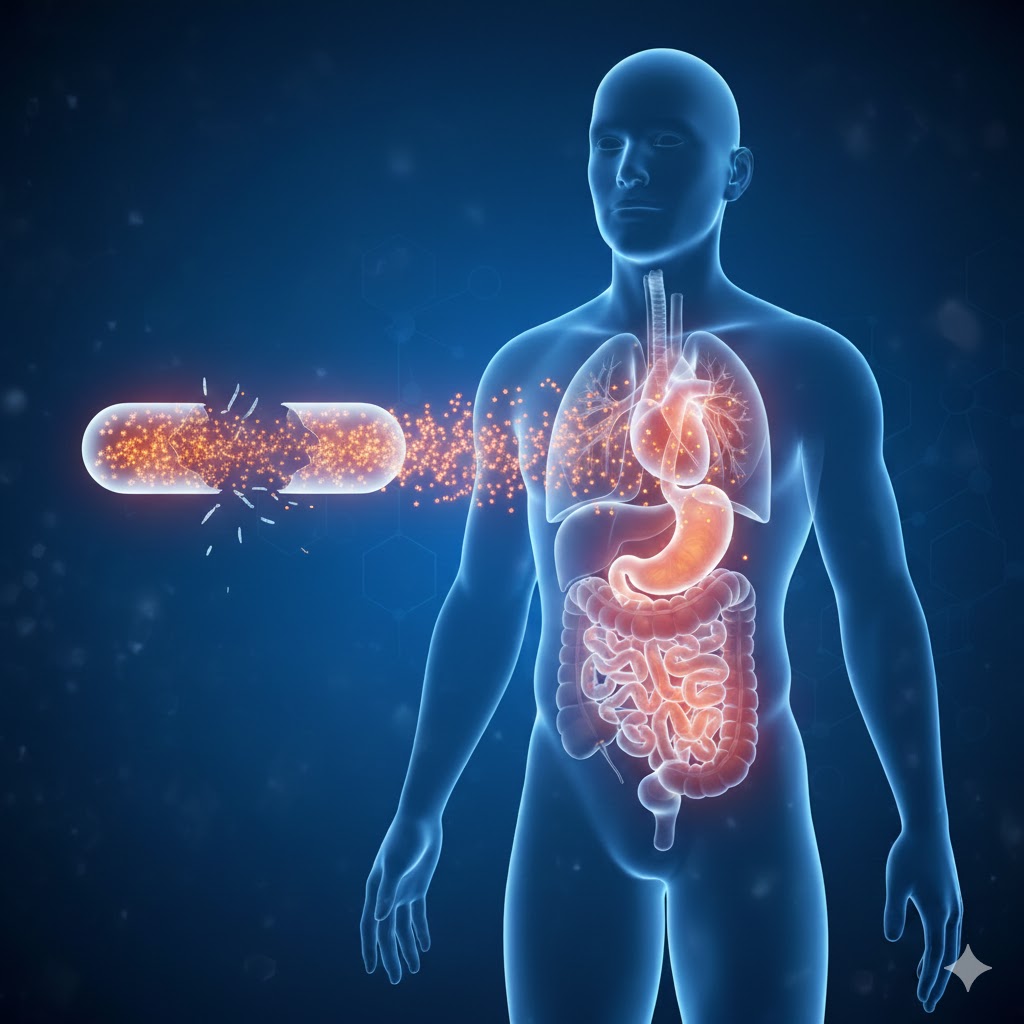

Oral route

The oral route uses tablets, capsules, syrups, or solutions swallowed by the patient18. It is the most common route because it is convenient, portable, and suitable for self‑administration.

However, drugs given orally must survive the acidic stomach environment, digestive enzymes, and first‑pass metabolism in the liver, which can reduce how much drug reaches the bloodstream. To address these challenges, many modified release oral formulations are used, such as enteric-coated tablets for acid-sensitive drugs or sustained-release capsules for chronic pain medicines18.

Parenteral routes

Parenteral routes bypass the gastrointestinal tract and deliver drugs through injections or infusions. Main subtypes include:

- Intravenous (IV): The drug is given directly into a vein, making onset very rapid and bioavailability essentially complete, which is crucial in emergencies such as sepsis or acute myocardial infarction19.

- Intramuscular (IM) and subcutaneous (SC): The drug is injected into muscle or subcutaneous tissue, from where it is absorbed more slowly, as seen with many vaccines and insulin preparations19.

- Intraosseous and other specialized injections: In critical situations where venous access is difficult, such as in some neonates or cardiac arrest, intraosseous access can deliver drugs through the bone marrow space20.

Parenteral delivery is beneficial for precise dosing and rapid action, but it is hard to self-administer and often requires trained personnel and sterile technique.

Inhalation route

Inhalation delivers drug directly to the respiratory tract, mainly through inhalers or nebulizers21. It is widely used in asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease because the drug can act locally in the lungs while limiting systemic exposure.

Particle size and proper inhaler technique are critical factors, as they directly determine how deeply drug particles penetrate into the airways and the effective drug dose that deposits rather than being lost to swallowing22. Consequently, modern inhalers, including dry powder and soft mist devices, are specifically engineered to improve this pulmonary deposition efficiency and enhance ease of use23-24.

Transdermal and topical routes

Transdermal delivery uses the skin as a portal for systemic therapy, often via adhesive patches that release a drug continuously over many hours or days; classic examples include nicotine patches for smoking cessation and fentanyl patches for chronic pain25. Topical delivery, in contrast, focuses solely on local action, as seen with creams for eczema or gels for acne25. For both methods, formulations must carefully balance skin penetration with safety, frequently incorporating enhancers, liposomes, or other carriers to improve passage through the skin barrier when systemic action or deep local penetration is required.

Mucosal and other special routes

Other important routes include:

- Sublingual and buccal: Tablets or films placed under the tongue or in the cheek provide rapid absorption into the bloodstream and bypass first‑pass metabolism, as with sublingual nitroglycerin for angina26.

- Nasal: Sprays or drops can deliver drugs both for local effects, such as decongestants, and for systemic therapy with quick onset. Examples include some rescue migraine treatments27.

- Ophthalmic and otic: Eye and ear drops or inserts deliver medications directly to ocular or auditory structures, minimizing systemic exposure28-29.

- Rectal and vaginal: Suppositories, foams, or gels can be useful when oral administration is not possible or when high local concentrations are needed30-32.

Conventional drug delivery systems

Traditional dosage forms remain the backbone of modern pharmacotherapy. Common systems include:

- Immediate‑release oral tablets and capsules that disintegrate quickly to release drug for rapid absorption33.

- Solutions and suspensions for oral or parenteral use, where the drug is already dissolved or finely dispersed. 34

- Topical preparations such as ointments, creams, lotions, and gels designed primarily for local action on skin or mucosa35.

These systems are relatively simple and cost‑effective but may lead to fluctuating blood levels and limited control over where the drug is distributed.

Controlled and sustained release systems

Controlled release systems aim to provide a more predictable, sustained exposure to a drug over an extended period. They are particularly valuable for chronic diseases where stable drug levels improve response and convenience.

Examples include:

- Extended‑release tablets that use polymer matrices or coatings to slow drug release over 12–24 hours36. This mechanism is seen with many once-daily antihypertensives or antidepressants.

- Depot injections, such as long‑acting antipsychotic formulations or contraceptive injections37. They release drug gradually from an oil base or biodegradable polymer after a single injection.

- Implants placed under the skin that provide months of continuous drug delivery38. They are used in some hormonal therapies and in treatments for opioid dependence.

These systems can reduce dosing frequency and help patients to adhere to the drug regimen, but they can be harder to adjust or reverse once administered.

Targeted and nanoparticle‑based delivery

Targeted drug delivery seeks to concentrate the drug in diseased tissues while sparing healthy organs39. This strategy is especially important in oncology, where conventional chemotherapy can damage many rapidly dividing normal cells.

Nanoparticle systems play a major role here. Common examples include:

- Liposomes: These are spherical vesicles with a lipid bilayer that can encapsulate both water‑soluble and fat‑soluble drugs and protect them from degradation40. Pegylated liposomal doxorubicin formulations, such as those used in some cancers and Kaposi sarcoma, are designed to exploit leaky tumor vessels so that the drug accumulates more in tumor tissue than in normal tissue41.

- Polymeric micelles: These are nanoscale assemblies of amphiphilic polymers that solubilize poorly water‑soluble drugs and can be functionalized with targeting ligands for tumors or inflamed tissues42.

- Solid lipid nanoparticles and related lipid‑based systems: These particles are made of solid or structured lipids that improve stability and bioavailability and are used in fields ranging from oncology to cosmetic formulations43.

The ability of these platforms to tune size, surface charge, and surface chemistry for optimized control over circulation time, cellular uptake, and immune recognition is a major advantage. However, they also raise new questions about long‑term safety, manufacturing complexity, and regulatory oversight.

Implants and device‑based delivery

Devices and implants provide physical platforms for precise, often long-term drug administration. Beyond simple subcutaneous rods for hormonal therapy, examples of these advanced systems include:

- Programmable infusion pumps that deliver insulin or chemotherapy at variable rates based on clinical need44-45.

- Drug‑eluting stents in cardiology, where a coronary stent slowly releases an antiproliferative drug to reduce restenosis after angioplasty46.

- Intraocular implants that provide sustained release of drugs to the back of the eye in chronic conditions such as some forms of uveitis47.

These systems achieve very high local concentrations with reduced systemic exposure but require procedural placement and careful follow‑up.

Challenges in drug delivery

Despite major progress, the field of drug delivery faces many significant challenges related to biological hurdles, safety, and practical implementation:

- Biological barriers in the body, such as the gastrointestinal tract, the skin, various mucus layers, and especially the blood–brain barrier, severely limit the types of drugs and formulations that can effectively reach their intended site of action48.

- Inter-patient variability in factors like genetics, comorbidities, and the use of concurrent medications significantly complicates the design of effective “one size fits all” delivery systems49.

- New materials used in advanced delivery systems must be rigorously demonstrated to be non-toxic and non-immunogenic before clinical use50.

- Manufacturing processes for complex delivery systems must be scalable and reproducible to enable mass production while maintaining consistent quality51-52.

- The costs associated with developing and producing advanced therapies must be kept manageable so that patients and health systems globally can afford and access these treatments.

Future directions

Future drug delivery is moving toward more personalized, precise, and responsive systems53. Personalized approaches aim to tailor not only the drug but also the delivery platform to an individual’s genetic profile, disease characteristics, and lifestyle. This can potentially improve efficacy and limit toxicity.

Emerging technologies include stimuli‑responsive systems that release drug in response to pH, temperature, enzymes, or external triggers such as light or ultrasound54. Advanced nanoparticles and hybrid materials are being engineered to cross biological barriers, deliver genes or RNA, and integrate with diagnostic tools55-56.

Taken together, drug delivery is no longer a passive step in therapy but an active field that shapes how medicines work, how safe they are, and how patients experience their treatment. As new drugs become more complex and more personalized, the science of delivering them effectively will remain central to modern healthcare.