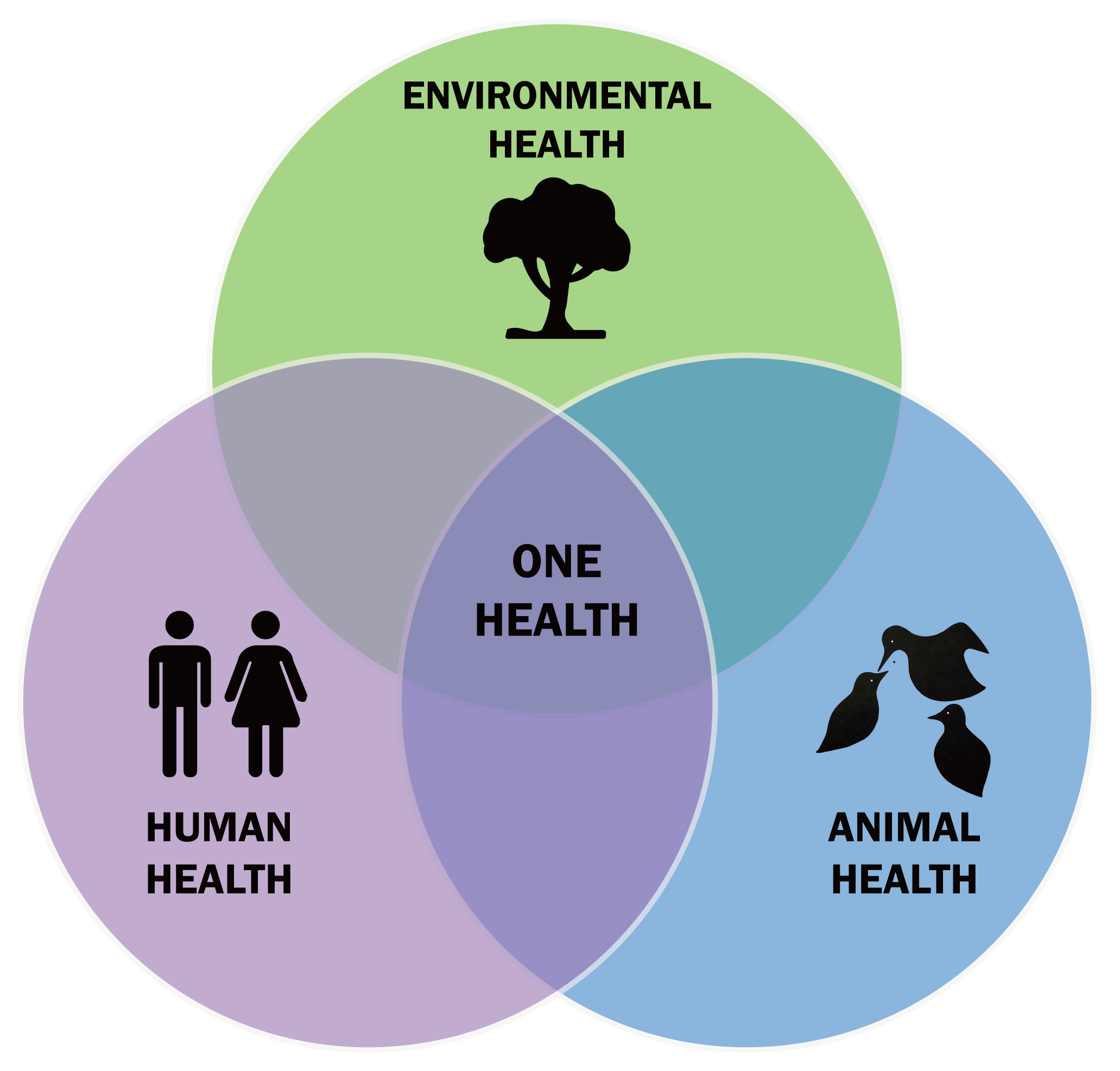

Imagine the well-being of a child in a thriving city, a robust herd of cattle on a distant farm, and a vibrant rainforest teeming with diverse wildlife. On the surface, they appear to have no connection at all, but in reality, these realms have deep interconnection. The principle of One Health is rooted in such an intricate relationship, calling for an integrated and unifying approach that recognizes the inseparable links between the health of humans, animals (both domestic and wild), and the environment we all share. This holistic perspective asserts that the well-being of any one component is intrinsically tied to the well-being of all.

A concept rooted in history

While One Health might sound like a new idea, only the term is new. The concept actually has its roots stretching back more than a century1. Visionaries such as Rudolf Virchow and William Osler understood long ago that diseases don’t respect the boundaries between species. However, One Health has gained urgency and formal recognition only in recent decades amidst the complexities associated with environmental degradation, a globalized world, and pandemics like COVID-19. In order to tackle the intertwined health challenges of our time, One Health offers a vital framework.

The core philosophy is balance, not hierarchy

At its core, One Health recognizes that health is a shared destiny, and so when one thread in the interconnected web is pulled or damaged, the effects ripple through the entire system. So, it calls for a sustainable balance—optimizing health outcomes across all three realms, instead of prioritizing humans above animals or the environment at the expense of the others2.

The pillars of One Health: building a collaborative framework

Good intentions aren’t enough to bring the philosophy of One Health to life. It demands collaboration across human and veterinary medicine, environmental science, public health, agriculture, ecology, social sciences, economics, and policy. Here, balance is also the central idea. No single discipline can solve these complex problems alone; collaborative efforts need to be effective3.

Firstly, all these sectors need to ensure timely communication, so data and insights are shared swiftly to prevent crises before they escalate. Secondly, there should be good coordination with aligned policies and strategies to avoid duplication and wasted resources. Finally, capacity building in training, infrastructure, and resources is a must, so each of these sectors can contribute effectively to the collaborative efforts.

Global challenges demanding a One Health approach

One Health is needed the most to deal with today’s global health challenges, such as zoonotic diseases, which are illnesses that jump from animals to humans4. Most new human infectious diseases, including COVID-19, Ebola, SARS, avian influenza, MERS, and rabies, originate in animals. And One Health helps us understand how these spillover events happen, allowing us to build integrated surveillance systems and eventually offer rapid, coordinated responses at the crucial interface where humans, animals, and the environment meet.

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is another critical issue that can only be dealt with the One Health approach5. This is because the accelerated rise of resistant microbes has resulted from the rampant misuse of antibiotics in human healthcare, livestock farming, and agriculture, combined with environmental contamination. Therefore, a unified, cross-sectoral approach that promotes responsible use of antimicrobials across all domains is the need of the hour.

Food safety and security are deeply linked to animal health, farming practices, and environmental conditions, and so they need to be viewed through the lens of One Health as well. Environmental degradation, such as deforestation, pollution, biodiversity loss, as well as climate change, are reshaping disease patterns, creating new reservoirs for pathogens. This is essential to consider because outbreaks in livestock or contamination of crops can quickly cascade into health crises—directly impacting the health of both humans and animals6,7. Such threats are quite dynamic in nature, as climate change is also causing the spread of vector-borne diseases like malaria and dengue to new regions8.

Even non-communicable diseases, such as diabetes and heart disease, are influenced indirectly by environmental factors and food systems, and therefore need to be guided by One Health principles9,10. Finally, water quality is a shared concern too, as contaminated water sources can devastate entire communities of people and animals alike, and so requires an integrated management using the One Health approach11.

Operationalizing One Health: from concept to action

How does One Health translate from concept into action? It’s about breaking down walls and building bridges. We need integrated surveillance systems that pool data from human, animal, and environmental health sectors to enable earlier detection of outbreaks12. Also, experts from diverse fields need to collaborate to assess the risks at the intersection of species and ecosystems. And when crises strike, be it pandemics or foodborne outbreaks, we need coordinated emergency responses to ensure that all sectors act in harmony13.

Policy alignment across ministries of health, agriculture, and environment is a must to ensure a truly holistic approach14. Interdisciplinary research is also essential as only that can unravel the complex interdependencies that drive health and disease15. Ultimately, community engagement is required to ground these efforts in local realities, making prevention and response more effective and sustainable16.

The far-reaching benefits of One Health

The benefits of embracing One Health are vast and far-reaching. It enhances global health security by improving preparedness and response to pandemics and epidemics. It supports sustainable development by promoting ecological balance and responsible resource management17. Public health outcomes improve dramatically through the reduction of the burden of zoonotic diseases and antimicrobial resistance.

Prevention of costly outbreaks in livestock and reducing healthcare expenses serves to safeguard livelihoods and national economies18. And, recognizing the intrinsic value of healthy ecosystems and biodiversity is central to maintaining overall health19. Ultimately, collaboration across sectors helps us use resources more efficiently, moving us beyond fragmented, piecemeal solutions toward integrated, holistic problem-solving.

Barriers and challenges on the road to One Health

Despite its promise, implementing One Health has its own set of challenges20:

- It is very hard to break through the stubborn traditional disciplinary silos, and it requires an ongoing effort to build trust among diverse stakeholders21.

- It is also paramount to ensure sustained political and financial commitment, but it is easier said than done.

- Technical and administrative hurdles often become barriers to sharing sensitive data across sectors required for collaboration.

- In addition, we need to strengthen the mechanisms to secure funding for intersectoral initiatives22.

- We also need to ensure that education systems evolve to prepare future professionals with One Health knowledge23.

- Ultimately, the critical barrier is to harmonize the legal and regulatory frameworks across sectors to ensure that coordinated action is taken when it is needed most.

Conclusion: a paradigm shift for the 21st century

One Health is no longer just a concept; it’s already creating a critical paradigm shift this century. There’s a clear consensus now that the health of humanity is inseparably linked to the health of animals and the environment. In a world facing unprecedented, interconnected challenges—from emerging infectious diseases to the pervasive threat of microplastics and heavy metals—it’s imperative we adopt a collaborative, holistic approach to ensure a healthier, more sustainable future for all life on Earth24.