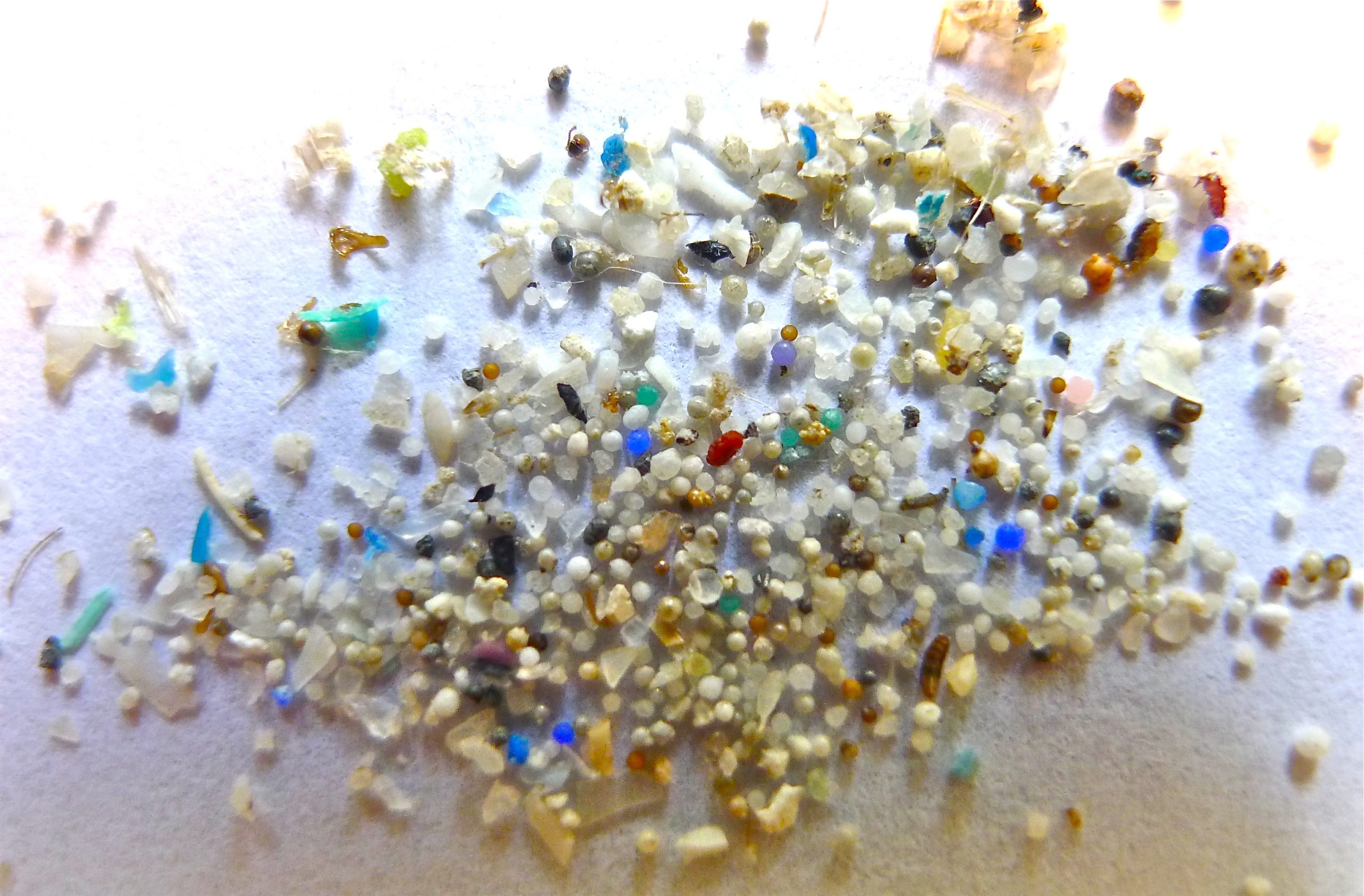

Microplastics have silently become one of the most persistent threats to our environment and health. These tiny fragments— smaller than five millimeters , sometimes invisible to the naked eye, are literally everywhere1! They’re in our oceans, soils, floating through the air we breathe, and, alarmingly, even inside our bodies. At first glance, they might come of across as just another nuisance, but the more we unearth, the more we realize that microplastics are rewriting the rules of pollution.

Where do microplastics come from?

It all starts with our love affair with plastic. Every plastic bag, bottle, piece of clothing, or tire eventually sheds tiny bits that don’t biodegrade; they just break down into smaller and smaller pieces. Washing synthetic clothes releases microfibers into the water, a single wash load of 6 kg can release up to 700,000 microplastic fibers2! Tires that wear down on roads release microplastics into the air and onto the ground— tire wear is, in fact, the largest source of microplastics in aquatic environments3. Cosmetics and personal care products often contain intentionally added microbeads for exfoliation4. Even compostable plastics that we deem “eco-friendly” can leave behind microplastic residue if conditions aren’t perfect.

Once released, these particles are nearly impossible to clean up. They slip through wastewater treatment plants, which typically capture only about 90% of microplastics, leaving millions of particles to enter our waterways daily5. They drift on the wind… microplastics have been found in remote mountain air, falling with rain and snow. They settle into rivers, lakes, and oceans. Researchers have even discovered them at the bottom of the Mariana Trench (the deepest point on Earth at nearly 11,000 meters) and in remote Arctic ice6, 7. There’s truly no place left untouched, scientists estimate that between 15 and 51 trillion microplastic particles are floating in our oceans alone8.

The impact on wildlife and food chains

The problem really starts when microplastics encounter life. Marine creatures such as plankton, fish, and shellfish often mistake these fragments for food. Ingesting microplastics can block their digestive tracts, affect their growth, even sometimes killing them9. Studies show that fish exposed to microplastics produce fewer offspring and have slower reaction times, making them more vulnerable to predators10. But it doesn’t end there. As smaller creatures are eaten by larger ones, microplastics move up the food chain, eventually finding their way onto our meals. One study found that people who regularly consume shellfish could be ingesting up to 11,000 microplastic particles annually11.

And it’s not just marine life at risk. Microplastics are now being found in soil at levels up to 23 times higher than in the oceans12. Agricultural soils are particularly susceptible, with sewage sludge used as fertilizer introducing millions of particles per kilogram. They contaminate compost, disrupt earthworm activity by altering gut microbiomes and reducing fertility, and can even be absorbed by crops through their root systems. Research shows that wheat and lettuce can take up nanoplastics through their roots and transport them to edible tissues13. That leads microplastics winding their way into our bread and vegetables!

Microplastics: chemical and biological hazards

Here’s where things get even more concerning. Microplastics are like little magnets for toxic chemicals14. They soak up heavy metals, pesticides, and persistent organic pollutants from their surroundings, concentrating toxins up to a million times higher than surrounding waters. Many plastics also contain their own harmful additives: phthalates, bisphenols, flame retardants, and PFAS that can leach out over time. When animals, including humans, ingest these particles, they’re not just consuming plastic, but also a cocktail of toxins.

Inside the body, microplastics have been shown (in lab studies) to cause inflammation , oxidative stress, and even DNA damage15. They can cross cellular membranes and accumulate in organs like the liver, kidneys, and brain. They can disrupt hormones and metabolism, with some plastic additives like BPA known to mimic estrogen16. And while we’re still learning about the long-term effects on humans, the early signs are troubling. Recent studies have detected microplastics in human blood , placenta, lung tissue, and even breast milk, suggesting these particles can travel throughout the body and potentially cross the blood-brain barrier17.

The biofilm menace: microplastics as superbug factories

Perhaps the most alarming twist in the microplastics saga is what ensues on their surfaces. Microplastics aren’t just floating debris, they are prime real estate for microbes14. Bacteria and other microorganisms rapidly colonize these particles, forming slimy biofilms within hours of entering the environment.

Within these biofilms, bacteria do something remarkable: they swap genes, including those that make them resistant to antibiotics. Studies have shown that microplastic biofilms can increase the rate of antibiotic resistance gene transfer via HGT by up to around 20 times compared to bacteria floating freely18. The rough, worn surfaces of aged microplastics provide even better attachment sites than fresh ones. Polyethylene microplastics, in particular, seem to be good at nurturing these microbial communities, and polyethylene happens to be the most commonly used plastic in the world, employed in everything from shopping bags to water bottles.

But why does this matter? Because these biofilm-coated microplastics can travel long distances, carrying antibiotic-resistant bacteria from one ecosystem to another. These tough little microbes have been found on microplastic surfaces at levels 100 to 5000 times greater than those in the surrounding seawater19. Wastewater treatment plants, rivers, and oceans become highways for the spread of superbugs, bacteria that can survive even our most powerful medicines. It’s a silent, invisible threat that could undermine decades of progress in fighting infectious diseases. The World Health Organization already considers antimicrobial resistance one of the top 10 global public health threats, and microplastics may be accelerating the crisis.

What can we do?

So, what’s the way forward? There’s no single solution available, but several steps can actually help. We need better waste management and stricter rules on plastics in compost and agriculture. Extended producer responsibility laws could make manufacturers responsible for the entire lifecycle of their plastic products. We need to develop and make use of substances that truly break down, and not just into smaller pieces, like cellulose-based alternatives that fully biodegrade20. Scientists are working on plastic-eating bacteria and enzymes (like PETase and MHETase) that can break down common plastics, and new cleanup technologies like floating barriers and filtration systems, but these are still in their early stages21-24.

As individuals, we can work towards reducing our plastic use by choosing reusable items, avoiding synthetic fabrics when possible, and properly disposing of what we do use. We can aim to support bans on single-use plastics and microbeads, while pushing for better recycling systems. At present, only about 9% of all plastic ever produced has been recycled25! But real change will come from reassessing our relationship with plastic altogether, moving from a disposable mindset to one that values durability, repair, and reuse.

And because microplastics touch every part of our world—from soil and crops to wildlife, livestock, and human health—the One Health approach is more important than ever26. Tackling microplastics requires coordinated action across environmental, agricultural, veterinary, and medical sectors, recognizing that the health of people, animals, and ecosystems are deeply interconnected. Only by bridging these gaps and raising awareness at every level can we hope to protect the future of our shared planet.

The unseen legacy

The threat posed by microplastics goes beyond visible pollution. It’s about unseen alterations to our environment, our food sources, and even the microscopic battles happening on the surfaces of these minuscule fragments. Unless we act, and soon, microplastics will continue to evade our notice, remaining tiny and enduring, while carrying risks that we are only starting to comprehend. With global plastic waste projected to triple by 2060, the problem will only escalate without decisive intervention27.

The legacy of microplastics could resonate for generations, unless we choose to rewrite the narrative now. The plastic we produce today might outlast our grandchildren’s grandchildren, but the choices we make can shape whether that legacy is one of growing harm or of innovation and restoration.